-40%

Loudoun Heights Virginia Harpers Ferry WV US Camp Dug Relic Bullet Bill Gavin

$ 13.19

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

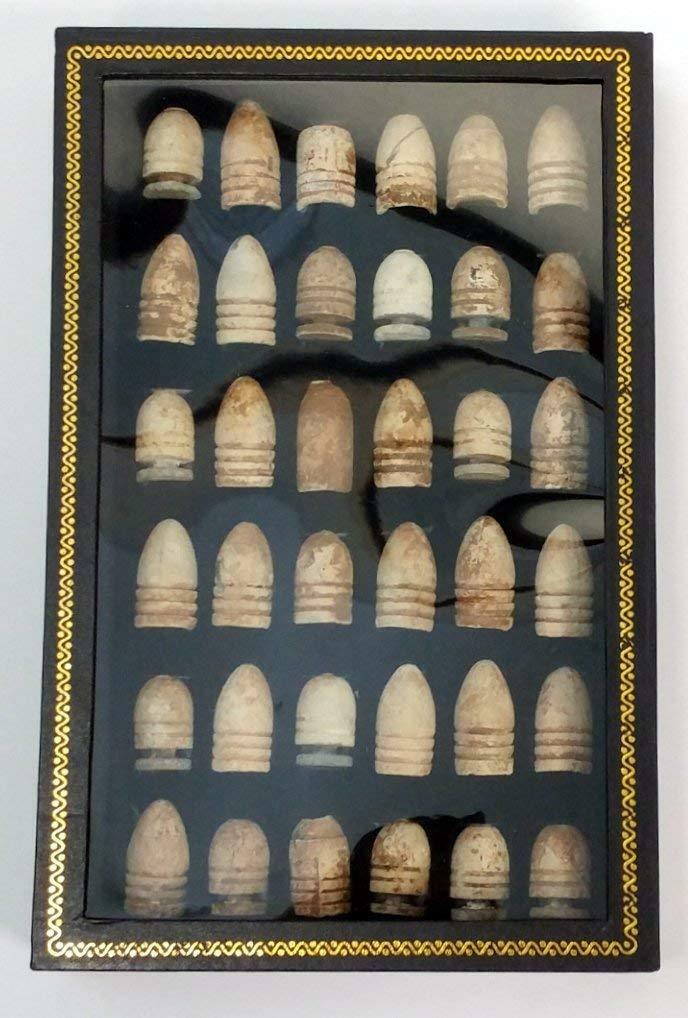

We are working as partners in conjunction with Gettysburg Relics to offer some very nice American Civil War relics for sale.LOUDOUN HEIGHTS VIRGINIA / ACROSS FROM HARPERS FERRY, WEST VIRGINIA / 1862 Union Winter Camp Site BILL GAVIN COLLECTION - A dropped .577 Caliber 3-Ring Bullet

This very nice dropped .577 Caliber 3-Ring Bullet was a part of the collection of the famous relic hunter Bill Gavin and was in a group of relics that were identified in his original display case as having been recovered from an 1862 Union Winter Camp Site on Loudoun Heights VA, part of the Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. Bill Gavin was the first relic hunter to use a metal detector to search for Civil War artifacts (back in the 1940s - the first location was Cold Harbor in 1946) and amassed a huge collection of items in the decades that followed. Gavin wrote four books, including the well-know "Accoutrement Plates North and South, 1861-1865" and several articles and was well respected for his knowledge in the field. He passed away in 2010. A provenance letter will be included with this relic.

Loudoun Heights during the Civil War-

In the midst of the 1862 Maryland Campaign, Gen. Robert E. Lee dispatched part of his army to Harpers Ferry, Virginia, (modern-day West Virginia), to engage with a force of more than 12,000 Federals in the Confederate rear area. After a day of Confederate bombardment from the surrounding high ground, Union infantry defending Harpers Ferry still held its ground on Bolivar Heights just west of the town. By the morning of September 15, Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson had positioned nearly 50 guns on Maryland and Loudoun Heights, and prepared to fire on the rear of the Federal infantry. During eleven hours of darkness, Jackson successfully deployed some 5,000 infantrymen and an additional 20 cannon in preparation for an attack. Shortly after dawn, Jackson began a fierce artillery barrage and ordered an infantry assault for 8:00 a.m. From Schoolhouse Ridge, Gen. A. P. Hill’s division was sent on a flanking move around the Federal left. Defending Federals under Col. Dixon S. Miles were shifted to meet the new threat, but Jackson’s guns had good effect. Miles ordered the surrender of the 12,000-man garrison shortly before being mortally wounded by a Confederate shell. The Federal surrender at Harpers Ferry was the largest surrender of United States forces until World War II.

Blood on the Snow- Cole vs Mosby on Loudoun Heights

January 7, 2017 / Travis

In the wake of their defeat at Five Points the survivors of Cole’s Cavalry returned to their winter encampment on Loudoun Heights to lick their wounds. The first few days were tense. One trooper later recalled how “For a time the men were cautions and never undressed at night. Then arms were kept always within reach and ready for use”. The campsite was well situated for defense. I lay on the east side of the Hillsboro Road, only a mile or so from the garrison at Harper’s Ferry. The campground was bound to the east and south by steep embankments that dropped into Piney Run. To the west rose the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The area was a familiar one for Cole and his men. They had spent much of their military service operating out of Harper’s Ferry. Many of his men were even native to the area. The Nicewarner brothers in Company D had grown up nearby, as had James Blinco, Reason Cross, and many others. Cole’s men recognized that if the ground was familiar to them it was also familiar to their enemy. “Loudon County was the home of many of Mosby’s officers and men…” wrote one veteran, “…Every path and ravine in the neighborhood of this isolated camp was, therefore, as familiar to Mosby and his men as the high road” .

As the temperatures plummeted and the snow fell Cole’s men turned their attention further and further from Mosby’s guerrillas and towards staying warm in their tents. Unfortunately for them the Confederate commander was putting a plan in motion to destroy Cole’s cavalry once and for all. The rival commands had been raiding and counter-raiding each other for months. After getting the drop on Hunter’s scouting party on New Years Day, Mosby figured now was the time to deliver a knockout punch. He was assisted in his plans by noted Confederate spy Frank Stringfellow. Stringfellow has already reconnoitered Cole’s camp and together he and Mosby developed a three-pronged attack plan .

On the afternoon of January 9th, 1864 Mosby and 106 men under his command left Upperville and headed north, passing through Purcellville and Hillsboro. Along the Hillsboro Road they encountered Stringfellow and his team of 10 men. One group of Mosby’s men under Captain Smith would attempt to steal the horses tied up at the camp hospital, while Stringfellow and his team would capture Major Cole in his headquarters, and Mosby himself would attack the sleeping cavalry camp. If all went as planned it would mean an end to the cavalry battalion that one northern observer declared “is of the same value to us that White and Mosby are to the rebels” .

The night was dark, cold, and clear. When the rebels got within a mile and a half from the sleeping troopers they turned eastward across country to the base of Short Hill Mountain. They skirted along the mountain, then along the bank of the Potomac, and finally up along a wooded ridge between the camp and Harper’s Ferry. Six inches or more of snow lay on the ground, muffling the rebel’s movements but also making the final climb a treacherous one. In making this roundabout movement Mosby was able to bypass or capture most of Cole’s pickets, who were primarily arrayed south of the camp along Piney Run.

By the time the rebels were ready to attack it was late. Accounts differ but it seems that the fight began between 3 and 4 AM. As the Confederates were approaching the camp they were challenged by a picket. When they refused to stop a shot rang out from a picket’s carbine. Mosby’s men charged from the wood line with a rebel yell and fired a volley into the first row of tents. At nearly the same time Stringfellow’s group charged on horseback towards the farmhouse where Major Cole was sleeping. In the darkness the two Confederate columns opened fire on one another, alerting the Union cavalrymen to their presence. Major Cole slipped out of the farmhouse as the rebels ran in, only narrowly escaping. He raced across the Hillsboro Road to rejoin his command. When he arrived he found a chaotic scene as the Confederates poured fire into his men’s tents. Cole’s men grabbed their weapons and resisted as best they could. Many braved the frigid weather without bothering to don boots or coats and fought off their assailants in shirt sleeves. Many years after the war Private Christopher Newcomer recalled the attack:

Cole’s men lay sleeping, many of them no doubt dreaming of their sweethearts and loved ones at home. No one who has not experienced a night attack from an enemy can form the slightest conception of the feelings of one awakened in the dead of night with the din of shots and yells coining from those thirsting for your blood. Each and every man in that attack, for the time, was an assassin. But we should remember that war means to kill; the soldier in the excitement of battle forgets what pity is, and nothing will satisfy his craving but blood.

The rude awakening brought Cole’s hardy veterans out into the deep snow covering the mountain, and they promptly picked up the gauge of battle. Long experience in border warfare had taught these gallant Marylanders to shoot at the horsemen, and not attempt to mount their own faithful chargers.

Captain George Vernon, one of Cole’s veteran officers, organized a line of resistance anchored on an old log cabin. He ordered his men to remain dismounted so that in the darkness they could differentiate friend from foe.

“Fire at every man on horseback!” Was almost the first order of the commanding officer. “Men, do not take to your horses!” The men obeyed both orders, and directed their fire upon every man on horseback, and this judicious action won them the day .

The battle raged on through the night. Private Newcomer also remembered the order to fire at those on horseback…

During the fight every man was for himself. There was no time to wait for orders, the cry rang out on the cold frosty air ” shoot every soldier on horseback.” Many of the Confederates who were killed or wounded were burned with powder, as Cole’s men used their carbines. It was hand to hand, and so dark, you could not see the face of the enemy you were shooting. It was a perfect hell! Every man cursing and yelling, and the horses were plunging and kicking in their mad efforts to get away. When one of the poor beasts would get wounded he would utter a piercing shriek that would echo throughout the mountain. Mosby’s men had emptied their revolvers. The night was too dark for them to see to reload their pieces. They were now completely at the mercy of Cole’s Rangers, who were using their carbines with good effect .

Seeing the tide of battle turning one of Mosby’s officers, Captain Smith, ordered his men to set the tents alight in order to give his men light enough to see their foes. Just as the orders left his lips a Sergeant from Cole’s command poked his head from a nearby tent and fired his carbine at the rebel Captain. Smith fell instantly with a bullet through the brain. Having done so much to lead the Union resistance Captain Vernon too fell wounded “with a ghastly wound in the head; as soon as his brave followers discovered that this gallant officer was shot the vengeful bullets of the hardy veterans flew the faster” .

By this time the fighting had attracted the attention of the garrison over in Harper’s Ferry. Although the town was only a mile away as the crow flies it was much further by the winding mountain roads. Alarms were sounding in the town as the garrison watched and listened to the gunfire erupting across the river. The 34th Massachusetts Infantry was roused out of bed and sent off to provide what assistance they could to their beleaguered comrades. By the time they arrived, though, the fight had already been won. Mosby hadn’t expected Cole’s men to put op such a stout resistance, and the early friendly fire incident had unnerved his men. After 45 minutes of fighting the rebel commander “gathered up his shattered forces and retired from the disastrous attack in the direction of Hillsborough” . Some of Cole’s troopers made an attempt to pursue the defeated rebels, but by and large the fighting was over.

The battle was a costly one for Mosby, in terms of experience if not in lives. One Confederate reported “five of our men were left dead in the camp” along with three others mortally wounded . Another rebel was captured and a number were wounded. Although the casualty list seems light, many of the men Mosby lost were experienced officers. Captain William Smith and Lieutenant Colston had been killed outright, and Lieutenant Thomas Turner was mortally wounded. He died soon afterwards in the home of a nearby farmer. Smith and Turner were regarded as “without a doubt…the two most efficient officers in the Battalion . Among the wounded were Lieutenant Beattie and Colonel Mosby’s younger brother William.

Cole’s account listed the Confederate losses as “1 captain, 2 lieutenants, and 2 privates killed, and 2 privates mortally wounded, and 1 prisoner” . He counted his own losses as 4 enlisted men killed and 16 wounded. He also listed the grievously wounded Captain Vernon, shot through the left eye. One number missing from Cole’s casualty report were the six prisoners taken by Mosby. These men were likely pickets captured during the initial assault. Robert Moore has done a great job looking at these men who were captured over at his blog here and here. Of the six men only one would survive his time as a prisoner of war. Looking at the service records for Cole’s Cavalry it looks like the Major’s numbers weren’t far off. At least six men appear to have been killed or mortally wounded that night. Among them were John Kerns of Berkeley County (West) Virginia and a number of Marylanders – Simon Staley and Samuel Stone of Frederick County, Harvey Null of Carroll County , and Abraham Sosey of Washington County (you can read more about Abraham here). The service records also show at least 11 men and officers wounded.

One of those wounded in the fight was a local boy named Reason Cross. He was born and raised just across the river from Loudoun Heights at Bolivar, (West) Virginia; his father worked as an armorer in Harper’s Ferry. He followed in his father’s footsteps and was working at the armory when the war began, and when his father died in January 1861 he stepped up to support his mother and six siblings. Census records indicate that he was only 16 or 17 when he entered service in Company D of the Maryland Home Brigade Cavalry in November 1861. His enlistment papers say otherwise, recording him as a 25 year old machinist from Harper’s Ferry (15). Whatever the case he served with Cole’s Battalion through 1862 and 1863, and was even promoted to bugler. During the late night battle on Loudoun Heights the young man was shot in the abdomen. Bleeding from what most considered to be a fatal wound young Reason was brought back across the river and taken to Boliver. There, in his mother’s home, he lingered for four more days before finally passing. The official cause of death was a gunshot wound to the bladder. Unlike many soldiers north and south Reason Cross at least had the comfort of dying in his own home surrounded by loved ones. After his death his mother applied for a pension and was awarded a month for the loss of her son who had been her means of support (16). He was laid to rest just up the street from his boyhood home in the Fairview Lutheran Cemetery.

Thank you for viewing!